<French: Click here><Japanese: Click here>

Mister Miyagi agreed to let me perform as a monkey in the Ramayana. This is a wonderful opportunity to take my research on the actor-as-puppet even further. Indeed, beyond observing from the outside, I can also observe from the inside by paying attention to my own sensations and to my body in the role of a mover. However, since I learned theater through a different method and my native language is different, I was able to notice some very interesting differences in my gestures and in how I receive the speech of the speakers.

Mister Miyagi agreed to let me perform as a monkey in the Ramayana. This is a wonderful opportunity to take my research on the actor-as-puppet even further. Indeed, beyond observing from the outside, I can also observe from the inside by paying attention to my own sensations and to my body in the role of a mover. However, since I learned theater through a different method and my native language is different, I was able to notice some very interesting differences in my gestures and in how I receive the speech of the speakers.

Right away, I noticed that the learning method is fundamentally different. As in traditional Japanese theater, transmission is done through imitation. During the first rehearsals, I always positioned myself at the back so I could closely observe the movements of the other actors, which I then tried to reproduce. Even though some movements were quite difficult at first, I eventually adapted to the group’s gestures. Even though my level of Japanese isn’t very good, I manage to understand and absorb the physical logic through this imitation-based transmission.

By contrast, in France, in most cases, it is almost impossible to learn theater through imitation. The acting methods most commonly taught in conservatories and theater schools are based on the principle of the “embodied actor,” inspired by Aristotle’s poetics and Stanislavski’s method. Whereas in traditional Japanese theater, and in Miyagi’s approach, the “actor is distanced” from their character (meaning the actor is aware that they are not the character), in France, we are taught to become the character and to merge our own emotions with theirs.

The Japanese actor is a “cool” actor who does not let their body be influenced by their emotions (note: this does not mean they feel nothing), which allows them to maintain a precise, almost mechanical gestural style that will be nearly identical from one performance to the next. It is not the actor who transmits their emotions to the audience; rather, it is the audience that projects emotions onto the image the actor has built with their body.

The Japanese actor is a “cool” actor who does not let their body be influenced by their emotions (note: this does not mean they feel nothing), which allows them to maintain a precise, almost mechanical gestural style that will be nearly identical from one performance to the next. It is not the actor who transmits their emotions to the audience; rather, it is the audience that projects emotions onto the image the actor has built with their body.

In the case of the embodied actor, the performer draws from memory (what we could call an “internal attic”) to access emotions they have felt during specific moments in their life, which might resemble those experienced by the character, in order to move toward realistic acting. The gestures are not defined in advance (only the spatial movements are), and they are completely influenced by what the actor is feeling on stage at that specific moment. Each performance will therefore be completely different from the others.

In other words, Western actors are not guided by an “internal music” like Japanese actors are, but by their emotions. It is therefore an inner process that cannot be transmitted simply by observing from the outside. To properly absorb this acting method, one must have a certain emotional sensitivity and an ability to summon past feelings.

Of course, this is not to say that one method is simpler than the other, since they each involve completely different mechanics. However, I find the imitation-based learning process more accessible. As Tadashi Suzuki said in Culture is the Body: beyond cultural differences, personal identities, and individual stories, what unites us all as human beings is our body.

Of course, this is not to say that one method is simpler than the other, since they each involve completely different mechanics. However, I find the imitation-based learning process more accessible. As Tadashi Suzuki said in Culture is the Body: beyond cultural differences, personal identities, and individual stories, what unites us all as human beings is our body.

An acting style based on mastery of the body is therefore much more egalitarian than one based on emotions. Anyone—regardless of where they come from or who they are—can, with enough training, achieve the same precision of movement as the actors at SPAC.

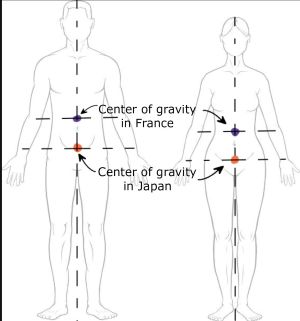

At SPAC, the body is governed by three essential axes: breath, the flow of energy throughout the body, and control of the body’s center, known as the “center of gravity”. The center of gravity is located below the belly, on the same line as the start of the hip joints. All parts of the body must be connected to this center of gravity; it is therefore very important to feel it at all times. When portraying the monkeys, the center of gravity is still placed in this same location.

However, Yuzu Sato, who was observing us during Scene 2 (when the monkeys discover the ocean for the first time), noticed that my posture was different from that of the other monkeys. I believe one of the reasons is that I am used to performing with a different center of gravity. In the West, the center of gravity is usually placed at the level of the diaphragm, just below the ribcage. The reason for this difference can be explained historically by a different hierarchy between body and text. In France, as in much of the Western world, the spoken text is often considered to be of higher importance than the body, whereas in Japan and across Asia, there is generally no such hierarchy—both elements are often regarded as being on the same level. While in Japan physical performance plays a fundamental role in theatrical expression, for a long time in France, theater was primarily seen as a declamatory art.

It is therefore natural for Westerners to place the center of gravity at the level of the diaphragm, since it is the most engaged muscle during speech projection.

As a result, I shift between two centers of gravity, which allows me to broaden the range of my movements. However, the downside is that I can lose my balance easily and often end up in uncomfortable and difficult positions to maintain. But I have discovered that my weaknesses can become strengths. Miyagi told us that a body is always more captivating to watch when it is in a desperate situation. According to him, a body full of confidence is a boring one. When an actor finds themselves in a desperate state, the audience will immediately wonder: what is happening to him ? What’s going on? What is he seeing?

However, my moments of distress and instability are mostly accidental, and while they may be beautiful in the moment, they are not repeatable. An experienced actor, on the other hand, can play with their limits and put themselves in difficulty deliberately, reproducing that state in every performance. That is something I aim to achieve.

During Scene 2 (when the monkeys discover the ocean), Yuzu, who was observing us during rehearsal, noticed that unlike the other monkeys, who were stretching their bodies upward to express the vastness of the sea, I was looking down at my feet. I think it’s because our approaches to the role were different. The others instinctively asked themselves: how can I represent, with my body, a monkey encountering the ocean’s immensity for the first time?

During Scene 2 (when the monkeys discover the ocean), Yuzu, who was observing us during rehearsal, noticed that unlike the other monkeys, who were stretching their bodies upward to express the vastness of the sea, I was looking down at my feet. I think it’s because our approaches to the role were different. The others instinctively asked themselves: how can I represent, with my body, a monkey encountering the ocean’s immensity for the first time?

Whereas my instinct was not to think with my body, but to recall the time when my sister and I used to play in the waves when we were children. I naturally applied the method of the embodied actor to my monkey, thinking: my monkey is like a five-year-old child. Children are more intrigued by the waves licking their feet than by the distant horizon.

I didn’t realize at first that my posture was completely different from the others. Yuzu thought my posture was good and that it allowed the sea to be represented in three dimensions.

While many people believe that these two acting methods are complete opposites, I actually think they are compatible and that they can enrich one another in many ways.

When it comes to how I receive the words of the speakers, it’s also very different. Since my level of Japanese isn’t very good, even though I know the play well, there are many words I don’t understand. So, when I hear a sentence or a word that I do recognize, it feels like it hits me all of a sudden, amplifying its power and allowing it to truly resonate within me.

The problem with repeating the same text over and over again is that one risks falling into a kind of automatism, where the text is heard but not truly listened to. A text will never have the same flavor as the first time it is discovered. This issue is common to actors all over the world. But in my case, I’ve noticed that as I gradually learn new words in Japanese, it’s as if I’m constantly rediscovering the text, and new words keep emerging from it endlessly. So I am almost always in a state of listening that feels like the first time.

Before coming to Japan, I had read interviews with Miyagi in which he said that “the words of the text should fall on the actors like rain”. At the time, I had trouble understanding what he meant by that comparison. But now, I completely understand his thinking, and I find the metaphor very accurate.

For the parts of the text that I still can’t understand in Japanese (even though I can follow along quite well thanks to the French translation I have memorized), I find that this actually becomes a useful tool for performance. In fact, the monkeys, magical as they may be, perhaps don’t speak Rama’s language at all. There are some words they might recognize (like dogs when you say “walk” or “dinner”), but they probably don’t possess Hanuman’s eloquence. So in a way, they’re a bit like me. That is to say, they try to understand what’s going on by interpreting the meaning of others’ gestures.

For example, in Scene 5, when Hanuman returns from Lanka, Rama weeps over the loss of his beloved. Even though I don’t understand most of the words he uses in Japanese, I can see his suffering and his sadness.

So I’ve noticed that compared to a play in French, which I can fully understand without much effort, here, my listening skills and my observation of the group have both improved.

It made me want to someday stage a play with people from many different nationalities who don’t speak each other’s language—to see them develop means of communication beyond speech, but also to observe how they receive words in the languages of others. Of course, Peter Brook already conducted similar experiments, but his actors all spoke English. I would like to take the experiment much further by staging a play with actors and an audience who do not understand each other’s language at all. Each person would have a completely different interpretation and vision of the play, and the words would take on an entirely new dimension.

Performing with SPAC is a great way to learn how to better use one’s body. It’s also an interesting experience for understanding the power of words and collective energy. Even though the entire show is in Japanese, it didn’t stop me from taking part. That’s what is so wonderful about this theater—it is inclusive and universal.

Janelle RIABI

Ramayana

https://festival-shizuoka.jp/en/program/ramayana/

Dates: 29 April at 18:45, 2 May at 18:45, 3 May at 18:45, 4 May at 18:45, 5 May at 18:45, 6 May at 18:45

Venue: Momijiyama Garden Square, Sumpu Castle Park

Duration: Approx 90minutes

Language: In Japanese with English surtitles

*Information about surtitles in other languages will be announced later.

Seat: Reserved-seating

Original work: Valmiki

Structure and direction: MIYAGI Satoshi